A Behind the Scenes Look at Caring for Our Collection

By: Liz Ale, Collections Assistant

As a member of the Eiteljorg Museum’s Collections Department, my main responsibility is caring for the items in the collection. The idea of “care” can vary across cultures and contexts. For example, caring for your grandfather’s World War II medal may involve passing it around the dinner table as you discuss his life and your family history to make sure that his accomplishments are never forgotten. Similarly, people from Native American communities may study items from earlier time periods to revitalize customary designs and techniques. Within a contemporary museum context, care involves handling and storing items in ways that ensure they will be preserved for as long as possible. With approximately 10,000 items located throughout the Eiteljorg Museum’s exhibits and storage vault, our department has no shortage of work to do!

Potawatomi Artist

Bandolier bag

Loom woven beadwork; glass beads, wool cloth, wool yarn, wool fox braid, cotton cloth

Museum purchase with funds provided by a grant from Lilly Endowment Inc.

To ensure that items in the collection are preserved for as long as possible, the Eiteljorg Collections staff works to mitigate the effects of “agents of deterioration”. Museum collections professionals use this phrase to describe things such as ultraviolet light, dust, humidity, acidic materials, pests, and other elements that can harm museum objects. Agents of deterioration can have different effects on museum objects depending on the item’s composition and the type and length of exposure. For instance, prolonged light exposure can cause organic dyes and watercolor paintings to fade, pests can chew through materials like plant matter and animal skins, and high humidity can cause metal to rust. Mitigating the effects of these agents of deterioration involves two main approaches: maintaining particular environmental conditions and storing items appropriately.

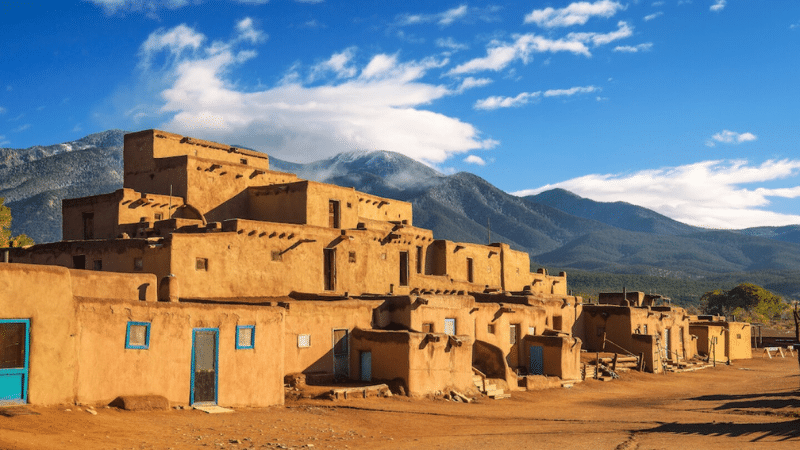

Scientific studies have shown that certain environmental conditions help to slow the rate at which museum objects deteriorate. Although optimal ranges vary based on material type, most items are best kept at 70 degrees Fahrenheit and 50 percent relative humidity (RH). Most of us are probably familiar with what 70 degrees feels like (as it’s an objectively PERFECT temperature for a spring day). Relative humidity is a bit harder to conceptualize. Technically speaking, RH is the amount of water vapor in the air relative to the maximum amount of moisture the air can hold at a given temperature. RH is why an 85 degree day in the arid Southwest is often more pleasant than an 85 degree day in muggy Florida. In my experience, 50 percent RH feels like an unnoticeable rate of humidity; the air around you neither feels too dry nor too humid. Museums must also keep light levels (or “lumens”) low to prevent damage to collections. The Eiteljorg uses low-lumen producing LED lights, filters that remove harmful UV rays from incandescent bulbs, and motion-activated lights to help protect items that are in storage or on exhibit.

A tray made from archival corrugated board and cotton ties.

The way we store items while they are off display also influences how long they will preserve. At the Eiteljorg, we use scientifically-proven storage methods that vary based on the object in question. Oil and acrylic paintings are stored upright on racks, large textiles such as weavings are rolled onto tubes to prevent creasing, and sculptures are placed onto heavy-duty shelving. Irregularly-shaped items often require custom-made storage enclosures. These handmade containers may support items that cannot stand on their own (like a piece of pottery with a rounded base), relieve pressure on fragile items (such as those with a delicate hinge or stitching), or protect objects from light and dust. To create these enclosures, members of the Collections Department use what are called “archival” materials. These materials, such as unbleached 100 percent cotton fabric, corrugated polypropylene plastic board, and acid-free tissue paper, are “inert”, meaning that they will not harm the objects they touch. Non-archival materials are avoided, as these can release harmful chemicals and cause items to warp or become discolored over time.

Huron-Wendat Artist

Wall pockets, mid-19th Century

Moose hair, caribou hide and hooves, quills, cloth, hide, metal

Gift of the Robert U. Sandroni and Lora A. Sandroni Family Trust

The next time you walk through the Eiteljorg Museum’s galleries, take a moment to consider the context in which the artwork in front of you is displayed. Are the lights dimmer than you would expect? Does the air around you feel temperate? Is the object on a mount that supports all of its fragile pieces? You now know that all of these small details are part of a larger goal: making sure that our collection is preserved well into the future.